Our Marketing Director, Tom, recently read a fascinating book called Dirty Old London: The Victorian Fight Against Filth, by Victorian aficionado and author Lee Jackson. He realised how striking the problems associated with waste over 150 years ago resonated with issues we experience today. Therefore, could Victorian waste management provide the answer to resolve waste issues in our contemporary society?

One of the largest waste products of Victorian London was ash from fires. Nineteenth century households and industry relied on fire for cooking, manufacturing and warmth. The first similarity was personal protective equipment (PPE). In the early 1800s, dustmen wore protective clothing such as flannel jackets, velveteen breeches and fan-tailed hats that covered the neck to offer some defence against the dirt the operatives were exposed to. Today the jackets include hi-vis bands and a hard hat replaces the fan-tailed counterpart.

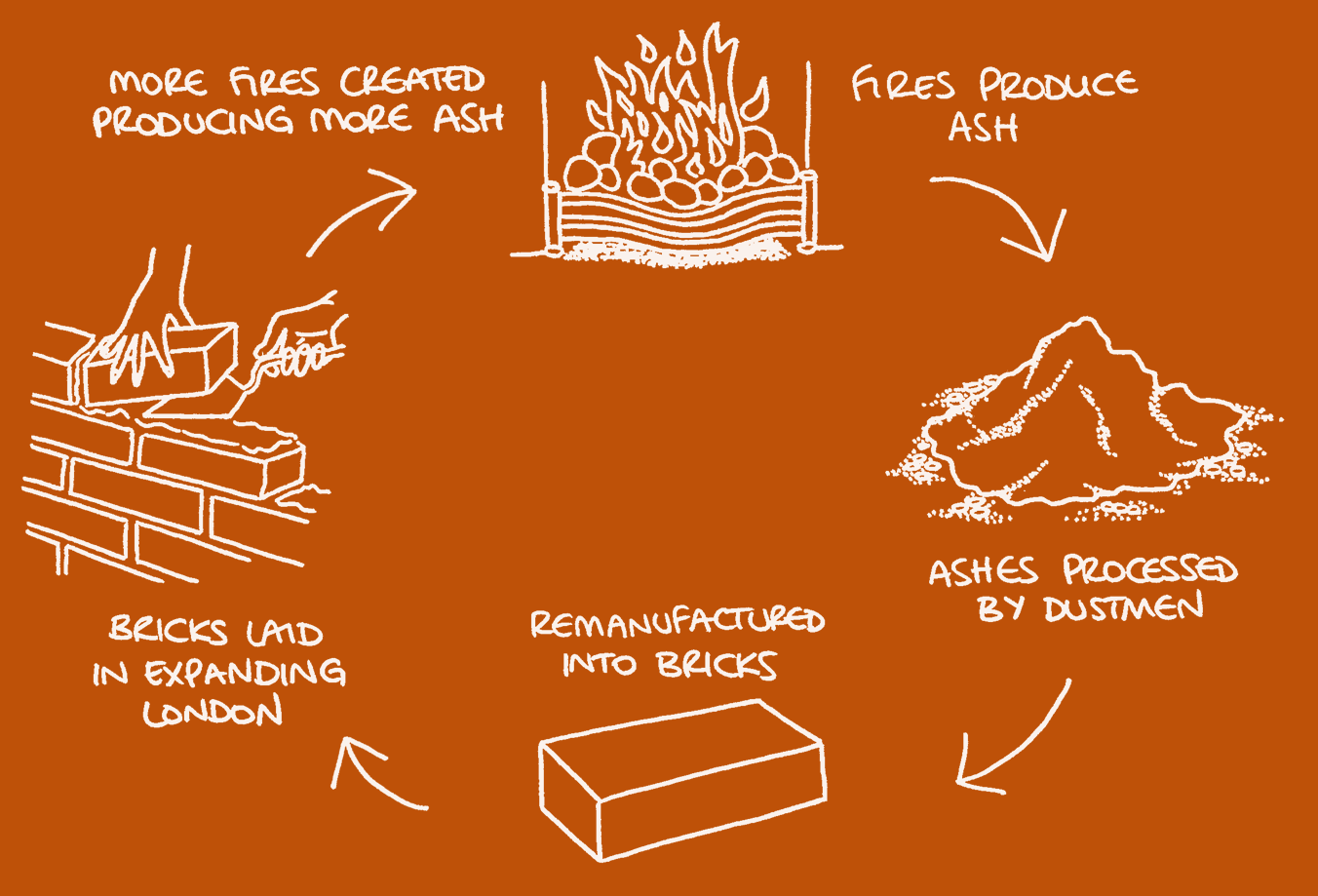

As like today, during the Victorian era waste management depended on supply and demand. Today PRN price fluctuations depend on the demand of certain recyclates. The same can be said for Victorian ashes. The idea of ‘collecting dust was a profit-making enterprise’ and ‘the profits for contractors lay in recycling.’ Brick making was a prime recycling option where ashes were worked into manufacturing. As London expanded the demand for bricks was unprecedented and the recycling of ashes boomed. This embodies the circular economy concept we are encouraging today; turning former waste into a new usable product. You could say Victorian London rose from its own ashes.

At certain points in London’s growth the ‘dust’ industry was cut throat, which is unsurprising as there was money to be had. Today, there is similarly an abundance of entrepreneurs in the waste industry, which remains intensely competitive. In Victorian London, unauthorised dust collections were performed by non-parish officials who realised they could get a quick quid by selling on the recyclate to brick makers. These law breakers were prosecuted and often fined which can be reflected in contemporary illegal waste operations that the Environment Agency tackles today.

When demand became more futile, costs increased for dust contractors. As more houses were built, there were more fires which created a surplus of ash. The volume generated exceeded the demand for brick making and materials for road building. Therefore, as demand dropped so did the selling price, once again reflecting PRN values of recyclates today.

The Victorians looked for ways to efficiently improve logistics and operations. This is evident with the local authorities, who mostly took over from the recycling dust contractors, by enabling daily collections from households as opposed to former ad hoc arrangements. Collection pails were standardised and dustbins changed very little well into the twentieth century. Today’s waste management society equally identifies the most effective methods of reusing and recycling, and new inventions to refine processes are regularly released.

When there was insufficient demand in brick making, ash deposits were in abundance. Unlike our revised idea today, it was apparent that ‘out of sight, out of mind’ was a way of thinking as these unusable deposits were effectively dumped, similar to sending general waste to a landfill site today.

At the end of the Victorian era and moving into the early twentieth century, there was an increase in gas fires, a decline in coal fires and electricity became more widespread. This in turn meant less ash. The costs associated with disposal were high but alternative solutions were still to be developed and implemented.

First developed in other UK industrial cities in the 1870s, incineration of waste was first introduced. The machines used were known as dust destructors and would essentially burn the ashes into ‘clinker’, weighing one eight of the original volume. This was then used as ballast in operations such as road making.

A feasibility study in London commenced in 1893 to implement a destructor in Shoreditch which could power a steam engine and generate electricity. The plant was constructed in 1897 and electricity was supplied to the local area, with surplus heat used to warm the local public bath located next to the plant. The idea attracted national attention and was recreated elsewhere in London. In a turn of events, the demand now outweighed supply. The volume of ashes could not meet the demand to produce enough electricity; in fact it only provided a miniscule fraction of the requirement.

Jackson neatly sums up the time ‘as a long and tortuous period of readjustment.’ We could say that we are still readjusting today. As recently mentioned in a previous RPS blog, the attitude towards waste management can challenge progression. In 2015, Irn Bru manufacturer AG Barr ceased collecting glass bottles for cleaning and reuse. The decision was made due to economic constraints making the deposit philosophy not viable. The director commented that: "it was the end of an era." However, the introduction of the latest packing technology by the business demonstrates the birth of a new one. The Victorians similarly didn't just continue to plod along with outdated technology. They embraced efficiency and developed new ways to process increased volumes of specific wastes.

The ideas that are currently underway or being developed now, for example large EFW plants, are by no means a new concept. Perhaps we could look to our own history to see if we can anticipate what may happen in the future of waste management.